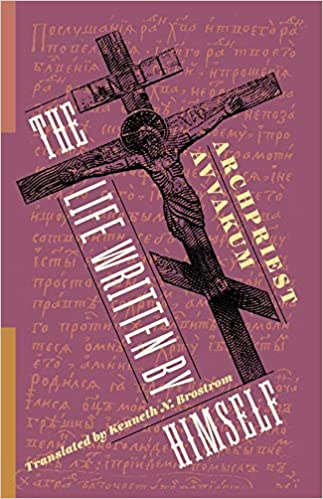

The Life Written by Himself

Disclaimer: This book was sent to me by the publisher in exchange for an honest review. As an Amazon Associate, I may earn commissions from qualifying purchases from Amazon.com.

I had the chance to read an early copy of an upcoming update to an old book. It’s called The Life Written by Himself by a Russian Archpriest named Avvakum Petrov. The book comes out at the end of May but you can preorder it now (see: Amazon link).

This book certainly isn’t for everyone. That’s to be expected from the fact that it shares the thoughts of a 17th-century priest who lived in poverty and persecution in Russia. Yet the older I get, the more I realize how much we stand to gain from reading really old books.

The updated intro itself is worth the book as it offers a fascinating historical setup to Avvakum’s life and times. Avvakum stood up against a version of Christianity that joined itself together with the government of Russia to gain power and influence. This is something the church in America would benefit to reflect on as well. Beyond this, there are two reasons you might find to appreciate this book.

The first reason—and the best takeaway from this book—is its perspective on the nature of suffering, especially for a Christ-follower. Despite the difference in culture and times, I was incredibly moved by his account. Avvakum is tortured in numerous ways throughout his lifetime and is eventually killed for his faith. Yet he lives with boldness in the face of suffering.

I came up, and the poor dear started in on me, saying, “Will these sufferings go on a long time, Archpriest?†And I said, “Markovna, right up to our very death.†And so she sighed and answered, “Good enough, PetroviÄ, then let’s be getting on.â€

Neither famine of bread nor thirst for water destroys a man; but a great famine it is for a man to live, not praying to God.

In the Chamber of the Cross the bishops disputed with me, then led me into the great cathedral, and after the Transposition of the Host they sheared the Deacon Fyodor and me, and then damned us, but I damned them in return. Almighty lively it was during that Mass!

Satan besought God for our radiant Russia so he might turn her crimson with the blood of martyrs. Good thinking, devil, and it’s good enough for us—to suffer for the sake of Christ our Light!

Most moving of all for me was the way Avvakum boldly lived out his faith, precisely when he recognized what it would cost him. Passages like this one are stunning (and show how amazing his wife was too):

Sitting there feeling heavy at heart, I pondered: “What shall I do? Preach the Word of God or hide out somewhere? For I am bound by my wife and children.†And seeing me downcast, the Archpriestess approached in a manner most seemly, and she said unto me, “Why are you heavy at heart, my lord?†And in detail did I acquaint her with everything: “Wife, what shall I do? The winter of heresy is here. Should I speak out or keep quiet? I am bound by all of you!†And she said to me, “Lord a’mercy! What are you saying, Petrovich? I’ve heard the words of the Apostle—you were reading them yourself: ‘Art thou bound unto a wife? seek not to be loosed. Art thou loosed from a wife? seek not a wife.’ I bless you together with our children. Now stand up and preach the Word of God like you used to and don’t grieve over us. As long as God deigns, we’ll live together, and when we’re separated, don’t forget us in your prayers. Christ is strong, and he won’t abandon us. Now go on, get to the church, Petrovich, unmask the whoredom of heresy!†Well sir, I bowed low to her for that, and shaking off the blindness of a heavy heart I began as before to preach and teach the Word of God about the towns and everywhere, and yet again did I unmask the Nikonian heresy with boldness.

The second reason you may enjoy this book is if you have an appreciation for Russian literature. Perhaps that is an even smaller category than the first reason I gave to read this book. Yet there is a lot here. In the past six months, I read both the Gulag Archipelago and Crime and Punishment (two iconic Russian books). Both impacted me deeply and continue to stir my thoughts.

Avvakum is considered Russia’s first modern writer. Therefore, reading him is a chance to “climb the tree” of ideas and trace many back to an early source (see: Climbing the Tree). The great novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky (who wrote Crime and Punishment) hilariously said, “I think that if one were to translate a piece such as the narrative of the Archpriest Avvakum, the result would be nonsense, or better, nothing whatever would come of it.” I think he was wrong on both accounts.

More favorably, another great Russian writer—Leo Tolstoy—“once said that he could not read the Life without weeping, and one supposes that he perhaps saw in Avvakum an ideal Russian with a Russian capacity to suffer and to remain steadfastly true to his understanding of the good.” I read the book more as Tolstoy did. If reading this book helps us with the capacity to suffer and remain steadfastly true to our understanding of the good, it would be well worth it.

Do You Want to Read the Bible Without Falling Behind?

Sign up your email and I’ll send you a PDF to download and use my custom-made reading plan system. There’s no way to fall behind on this system and every day will be different no matter how long you use it!

I’ll send future content directly to your inbox AND you can dive into the Bible like never before.